If you are a big optical illusion aficionado and think you have seen it all, it's time to reconsider. Because this optical illusion is not just puzzling for the brain, but also tricks human reflexes at a physiological level. Yes, that’s right. This is certainly not for the faint-hearted. This illusion, introduced in a 2022 study, is published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

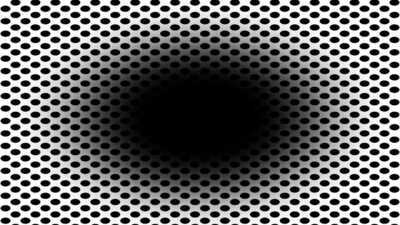

Expanding hole

Look at this image. Do you see the central black hole expanding, as if you’re moving into a dark environment, or falling into a hole? If so, you’re not alone! This fascinating illusion, known as the ‘expanding hole’, is perceived the same way as you did by 86% of the population.

This powerful visual phenomenon gives the impression of falling into a dark void, and according to scientists, it results in a physiological response - pupil dilation!

A mystery to scientists

This optical illusion has also grabbed the attention of scientists. "The 'expanding hole' is a highly dynamic illusion: The circular smear or shadow gradient of the central black hole evokes a marked impression of optic flow, as if the observer were heading forward into a hole or tunnel,” Dr Bruno Laeng, first author, and professor at the Department of Psychology of the University of Oslo, said in a statement.

If you though optical illusions are mere gimmicks, scientists disagree. For the ones in the field of psychosociology, illusions are useful tools to understand how our visual system interprets the world, much more complexly than a simple device that just measures light.

In this study, the researchers found that the 'expanding hole' illusion is so good at deceiving our brain that it even prompts a dilation reflex of the pupils to let in more light, just as would happen if we were really moving into a dark area.

Pupil reflex and perception

"Here we show, based on the new 'expanding hole' illusion that that the pupil reacts to how we perceive light, even if this 'light' is imaginary like in the illusion, and not just to the amount of light energy that actually enters the eye. The illusion of the expanding hole prompts a corresponding dilation of the pupil, as it would happen if darkness really increased," Laeng said.

The researchers also looked at how the color of the hole (besides black: blue, cyan, green, magenta, red, yellow, or white) and of the surrounding dots affect how strongly humans react (mentally and physiologically) to the illusion.

To test the illusion’s strength, the researchers presented 50 participants (women and men) with with normal vision, to rate subjectively how strongly they perceived the illusion. When the participants gazed at the image, the researchers measured their eye movements and their pupils' unconscious constrictions and dilations. For comparison, they also showed ‘scrambled’ versions of the image with the same brightness and colors but no clear pattern.

The findings

What they found was striking. The researchers noticed that the illusion was most effective when the hole was black. Fourteen percent of participants didn't perceive any illusory expansion when the hole was black, while 20% didn't when the hole was in color.

They concluded that black holes led to strong reflex dilations of the participants' pupils, while colored holes prompted their pupils to constrict. For black holes, the more strongly participants felt the illusion, the more their pupils tended to change in size. This link wasn’t seen with colored holes.

Video

Some were not susceptible

The researchers found that a minority were unsusceptible to the 'expanding hole' illusion. They are unsure why. They also don’t know whether other vertebrate species, or even nonvertebrate animals with camera eyes such as octopuses, might perceive the same illusion as we do.

"Our results show that pupils' dilation or contraction reflex is not a closed-loop mechanism, like a photocell opening a door, impervious to any other information than the actual amount of light stimulating the photoreceptor. Rather, the eye adjusts to perceived and even imagined light, not simply to physical energy. Future studies could reveal other types of physiological or bodily changes that can ‘throw light’ onto how illusions work," Laeng added.

Expanding hole

Look at this image. Do you see the central black hole expanding, as if you’re moving into a dark environment, or falling into a hole? If so, you’re not alone! This fascinating illusion, known as the ‘expanding hole’, is perceived the same way as you did by 86% of the population.

This powerful visual phenomenon gives the impression of falling into a dark void, and according to scientists, it results in a physiological response - pupil dilation!

A mystery to scientists

This optical illusion has also grabbed the attention of scientists. "The 'expanding hole' is a highly dynamic illusion: The circular smear or shadow gradient of the central black hole evokes a marked impression of optic flow, as if the observer were heading forward into a hole or tunnel,” Dr Bruno Laeng, first author, and professor at the Department of Psychology of the University of Oslo, said in a statement.

If you though optical illusions are mere gimmicks, scientists disagree. For the ones in the field of psychosociology, illusions are useful tools to understand how our visual system interprets the world, much more complexly than a simple device that just measures light.

In this study, the researchers found that the 'expanding hole' illusion is so good at deceiving our brain that it even prompts a dilation reflex of the pupils to let in more light, just as would happen if we were really moving into a dark area.

Pupil reflex and perception

"Here we show, based on the new 'expanding hole' illusion that that the pupil reacts to how we perceive light, even if this 'light' is imaginary like in the illusion, and not just to the amount of light energy that actually enters the eye. The illusion of the expanding hole prompts a corresponding dilation of the pupil, as it would happen if darkness really increased," Laeng said.

The researchers also looked at how the color of the hole (besides black: blue, cyan, green, magenta, red, yellow, or white) and of the surrounding dots affect how strongly humans react (mentally and physiologically) to the illusion.

To test the illusion’s strength, the researchers presented 50 participants (women and men) with with normal vision, to rate subjectively how strongly they perceived the illusion. When the participants gazed at the image, the researchers measured their eye movements and their pupils' unconscious constrictions and dilations. For comparison, they also showed ‘scrambled’ versions of the image with the same brightness and colors but no clear pattern.

The findings

What they found was striking. The researchers noticed that the illusion was most effective when the hole was black. Fourteen percent of participants didn't perceive any illusory expansion when the hole was black, while 20% didn't when the hole was in color.

They concluded that black holes led to strong reflex dilations of the participants' pupils, while colored holes prompted their pupils to constrict. For black holes, the more strongly participants felt the illusion, the more their pupils tended to change in size. This link wasn’t seen with colored holes.

Video

Some were not susceptible

The researchers found that a minority were unsusceptible to the 'expanding hole' illusion. They are unsure why. They also don’t know whether other vertebrate species, or even nonvertebrate animals with camera eyes such as octopuses, might perceive the same illusion as we do.

"Our results show that pupils' dilation or contraction reflex is not a closed-loop mechanism, like a photocell opening a door, impervious to any other information than the actual amount of light stimulating the photoreceptor. Rather, the eye adjusts to perceived and even imagined light, not simply to physical energy. Future studies could reveal other types of physiological or bodily changes that can ‘throw light’ onto how illusions work," Laeng added.

You may also like

Watch: Flash floods submerge vehicles as heavy rain lashes Washington DC; rescue ops under way

Income Tax Return Alert: Falsely Claiming Deductions? Time to Be Careful!

Liverpool's scary 25-man Premier League squad if Reds make three more signings

PM Modi applauds TVS Motor Company for chronicling the beauty of Kutch

Tamil Nadu's Mettur dam reaches full capacity for third time in 2025, flood alert issued